When we hear these words, “Survival of the Fittest,” we often think of Darwin’s reflections on human evolution propelled by natural selection of distinctive traits that ensure endurance and development of the species.

“Survival of the fittest” also refers to our abilities to prevail during challenging times.

One of the best examples of how we can cope with severe adversity comes the polar adventures of Captain Robert Scott on the Terra Nova Expedition (1910-13) We all know of his valiant march, pulling sleds toward the South Pole, arriving only to find that Norwegian Roald Amundsen and his huskies had beaten him by about a month in December, 1911. All five of Scott’s polar party perished upon return to Cape Evans.

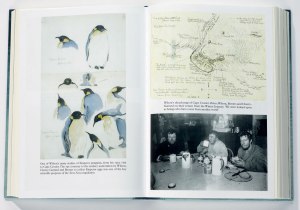

Another harrowing tale of survival from this ill-fated expedition is told in Apsley Cherry-Garrard’s The Worst Journey in the World. He, Birdie Bowers and Dr. Edmund Wilson set off from Cape Evans in the dead of the polar night (July, 1911) on “the weirdest bird nesting expedition” to Cape Crozier to find and capture Emperor Penguin eggs. It was Wilson’s theory that these flightless birds were related to dinosaurs and he wanted to see them in embryonic state, to do what scientists do, gather evidence.

The horrors these men experienced were almost unimaginable, temperatures down to -60 F., yawning and almost invisible crevasses, howling winds and terrain sometimes illuminated only by the Aurora Australis.

Cherry-Garrard, writing in The Worst Journey, noted:

“Our troubles were greatly increased by the state of our clothes. If we had been dressed in lead we should have been able to move our arms and necks and heads more easily than we could now. . .”

Death was welcomed:

“Such extremity of suffering cannot be measured; madness or death may give relief. But this I know: we on this journey were already beginning to think of death as a friend.”

How did they survive?

A positive attitude

“Things must improve,” Uncle Bill Wilson, the leader, doctor and scientist, kept saying over and over again. “Things will get better.”

Singing

“Birdie” Bowers sang his way home after capturing three Emperor eggs and having their tent blown away by a ferocious blizzard:

“I was resolved [he wrote afterwards] to keep warm and beneath my debris covering I paddled my feet and sang all the songs and hymns I knew to pass the time. I could occasionally thump Bill, and as he still moved I knew he was alive all right—”

“Stick it in the neck”

This was Cherry-Garrard’s often repeated encouragement-builder:

“I did want to howl many times every hour of these days and nights, but I invented a formula instead, which I repeated to myself continually. Especially, I remember, it came in useful when at the end of the march with my feet frost-bitten, my heart beating slowly, my vitality at its lowest ebb, my body solid with cold, I used to seize the shovel and go on digging snow on to the tent skirting while the cook inside was trying to light the primus [stove]” for a much-needed meal.

His formula, his mantra, his power-restorer sounded like this:

`You’ve got it in the neck—stick it—stick it—you’ve got it in the neck,’ was the refrain, and I wanted every little bit of encouragement it would give me; then I would find myself repeating `Stick it—stick it—stick—stick it—‘ and then `You’ve got it in the neck.’

In the end, all three men survived this weird bird nesting expedition. Why did they go? “For science,” wrote Cherry-Garrard, “in order that the world may have a little more knowledge, that it may build on what it knows instead of on what it thinks.” Don’t rest on faulty assumptions, get the facts.

And what did he think of his companions who also used all their strengths to survive this expedition:

“These two men [Wilson and Bowers] went through the Winter Journey and lived; later they went through the Polar Journey and died. They were gold, pure, shining, unalloyed. Words cannot express how good their companionship was.” (emphasis added)” 1922/37.

Survival depends upon those strengths we learn as children and young adventurers, those we can readily muster when the challenges become seemingly overwhelming.

High expectations, singing to keep up one’s spirits and keeping up a constant refrain that says, “I/we can do this. We will succeed.”

This is what contemporary psychologists call a positive or growth mind set.

Failure is not an option, in other words.

of these mysteries and constantly search for answers and more questions.

of these mysteries and constantly search for answers and more questions.